It is not necessary to understand things in order to argue about them.

– C. de Beaumarchais

|

Mexico’s Other Volcanoes |

| Hola! Jennifer and I spent a week in

Mexico over Christmas break 1998 and climbed 8 peaks other than the Big 3.

Leaving from the office party, we arrived in Mexico City late on December

18th. Rodulfo Araujo met us at the airport and whisked us to his home in the

city. We were electronically introduced to Rodulfo by George Bell Jr., who

is working on a comprehensive list of North America’s 14ers. We had carried

on a lively email conversation with Rodulfo for two months prior to our trip.

Rodulfo is one of Mexico’s scholars for peak names, altitudes and mountaineering

history. |

| With only a few hours rest, we rose

early Saturday and joined Rodulfo’s friends from the Grupo de los Cien for

a climb of Teyotl - Izta’s hair. It was like a CMC trip Mexico style. We drove

in two 4WD vehicles to the town of Aztacualoya north of Amecameca where we

enjoyed a street vendor breakfast and a quick visit to an old church. Beyond,

in the village of San Rafael, we took a series of improbable turns and started

up the dirt road toward Izta’s northern ramparts. Soon we had to show our

permit, which Rodulfo had secured the day before. The local landowners have

put a gate on the road and charge admission to the heights. Beyond, the road

climbed steadily to a junction with another road from the north. This northern

road, while a longer drive from Mexico City, would avoid the local’s gate.

The road to the junction could be driven with a rent-a-bug, but above the

junction we were glad to be in 4WD vehicles. We finally parked at 12,500 feet.

We had peek-a-boo views of Izta’s Cabeza, and the rock summits Yautepemes

and Solitario. I kept a rope in my pack in hopes of visiting one of the latter

summits before day’s end. |

| The hike up Teyotl’s west ridge was

wonderful. The north face of La Cabeza is one of Mexico’s wildest alpine faces,

and we had uninterrupted views of it as we rose. We lounged on Teyotl’s 15,420-foot

summit for some time enjoying our Mexican picnico. We had gone from the office

party to this lofty perch in less than 24 hours. We like this kind of time

travel. Teyotl, Izta’s hair, is a significant summit rising over 600 feet

from the saddle with La Cabeza. It has many sub summits to the north, and

it commands a large area. Teyotl means, “Where the rocks are born.” |

|

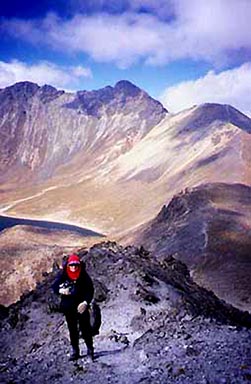

Jennifer and Rodulfo heading up Teyotl’s nascent rocks |

| We rapidly descended a scree gully

into the valley between La Cabeza and Teyotl, and visited the Teyotl hut.

The Grupo de los Cien works hard to build and maintain Mexico’s huts. They

believe the huts should be free, clean and open for all to use. In a series

of cleanup expeditions with other clubs, they removed nine metric tons of

trash from Izta. The Teyotl hut is in a wonderful position under La Cabeza

and we want to return to this valley for other climbs. From this hut you could

climb La Cabeza, Izta via La Arista de Luz, Teyotl, Yautepemes and Solitario.

On our way down I looked longingly at Solitario but our time was gone, and

we hustled back to the vehicles. The rope stayed in my pack. I’ll be back. |

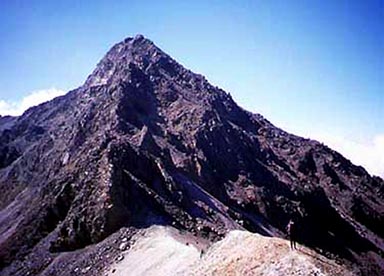

|

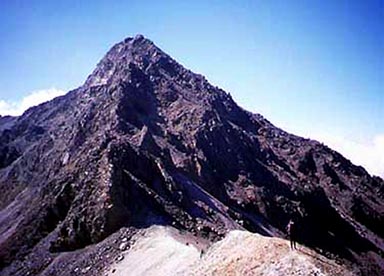

Solitario, the one that got away |

| On Sunday, Rodulfo and his friend Ruth

took us to the old volcano Ajusco southwest of Mexico City. Ajusco, at 13,077

feet, is Mexico City’s Green Mountain. There is a paved road around the peak

and you have a choice of three trails. We ascended from the north and ended

up on the northwest ridge of the old blown out crater. On the way up we heard

several large booms, and thought Popo was blowing its top. We hustled up to

the summit for a view, but Popo was docile. The booms were fireworks. When

Popo does burp it just adds to the celebration. We descended the northeast

ridge to complete a ring around the crater and exchanged email addresses with

a group on the sub summit called Aguila, which means eagle. |

|

En route on Ajusco’s northwestern crater rim |

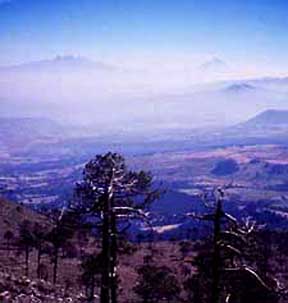

|

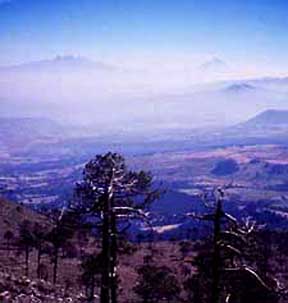

Izta (L) and Popo from Ajusco’s summit |

| We stopped at a swank pizza joint in

town where Rodulfo’s mother Lucy joined us. A Mexican rock band belted it

out on a giant screen nearby. At one point the music took a dramatic pause,

then the band chorused “Ajuua!” I said, “Hey! That’s the name

of the new Mexican restaurant near our house. What on Earth does Ajuua mean?”

Lucy smiled, and 10 minutes later we had the answer. In the old days when

Spanish galleons plied both oceans with their precious cargo, mule trains

moved the cargo across south-central Mexico. It was a tricky, theft-threatened

job. The families that chose to do it used obscure routes through the mountains.

Many narrow passages would not allow mule trains to pass each other and the

families used Huacos, or yells, to signal their approach to a tough section

of trail. Like a brand, each family had its own Huaco. Ajuua is a Huaco. Only

a few Huacos have come forward into the modern language, and they are used

in Mexican music. The Mariachi bands use them frequently and, as we learned,

the rock bands do as well. The best single word translation for Ajuua is “Yeah!” |

| On Monday we said good-bye to Rodulfo

and Lucy. Their hospitality was amazing, and we look forward to seeing them

in Colorado sometime. With Rodulfo’s detailed directions we putted off in

our rent-a-bug, and parked at Llano Grande on the Paseo between Mexico City

and Puebla. A good trail took us north through the forest to 13,386-foot Telepon.

The summit was adorned with many Christian statues. We gazed north to neighboring

Tlaloc and decided to go for it. The traverse was three miles through the

forest, and it was the best Hansel and Gretel hike we have done. We walked

through fairylands at speed, then dodged small cliff bands high on Tlaloc.

The approach to Tlaloc’s summit was a surreal journey through a rock playground.

On the 13,615-foot summit we found the ruin of a small Aztec city. There were

two parallel, arrow-straight lines of rocks. It was some sort of Aztec observatory.

We hustled back to the saddle, then following Rodulfo’s advice, hiked down

the road to the village of Rio Frio instead of re-climbing Telepon. It was

good advice. We reached Rio Frio in the last light, padded through town dodging

packs of dogs and caught a bus back up to the pass. We could not have climbed

back over Telepon that fast. To end this incredible day, we drove into the

night and finally found La Trinidad, a resort hotel in the tiny village of

Santa Cruz south of Apizaco. |

|

Looking south from Telepon’s summit at Izta (L) and Popo |

|

The Aztec observatory on Tlaloc’s summit |

| In the morning we paused in La Trinidad’s

sun-drenched courtyard, then took off for La Malinche. Our plan was to do

it as a day climb from La Trinidad. The road, which goes to just below treeline

on La Malinche, is now closed at 10,800 feet and you have to walk farther.

It’s a pleasant walk through the forest however and the climb above treeline

is simple and short. We summited 14,636-foot Malinche apace, then continued

south to 14,596-foot Chichita and 14,536-foot Octlayo. These sub summits provide

simple scrambles, are very photogenic and well worth the side trip. On the

way down, we also summited 13,520-foot Chiche, La Malinche’s prominent north

peak. Racing darkness, we zipped back to La Trinidad in time for a late dinner. |

|

Passing treeline en route up La Malinche |

|

Jennifer approaching La Malinche’s summit |

|

Looking southwest from La Malinche’s summit at Chichita (L) and Octlayo |

|

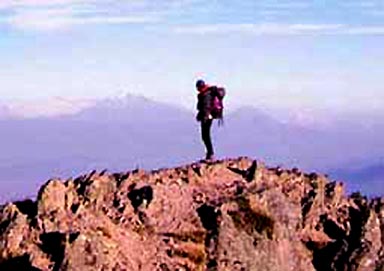

Jennifer on Chiche’s summit with Orizaba (L) and Sierra Negra in the distance |

| Pulled by the views that we had from

La Malinche, the next day we continued east and made an “ascent”

of 14,049-foot Cofre de Perote. Cofre is a large, gentle volcano north of

Orizaba, which is capped by a stubby, hundred-foot high rock tower. Cofre

means chest as in a storage container. We drove south up the road from the

town of Cofre until our peak baggers’ conscious made us park and start walking.

We parked at 12,600 feet, but it’s possible to drive rent-a-bugs to 14,000

feet on this peak. Those who are ambivalent about wilderness should visit

Cofre’s summit to better understand what it is we are fighting for. The summit

is festooned with radio, TV and microwave towers. We also visited 14,019-foot

Cofre Minor before retreating to Senior Reyes in Tlachichuca in hopes of meeting

some interesting climbers, but we found the place nearly deserted. |

|

Cofre de Perote from the north |

|

Cofre’s chest of horrors |

| On Christmas Eve day we did a day climb

of 14,993-foot Sierra Negra - Orizaba’s prominent south peak. Sierra Negra,

rising over 1,700 feet from its saddle with Orizaba, is Mexico’s fifth highest

peak. We believe the 14,993-foot elevation is low; the peak is closer to 15,200

feet. A road approaches from the southeast and, recently improved, now goes

all the way to the summit. Towers are appearing there now as well. This must

be the highest road in North America. It was not there when Gerry climbed

Sierra Negra in 1995. The road was the steepest challenge yet for our rent-a-bug,

but we managed to reach 12,600 feet. With care, you could drive all the way

into the Sierra Negra - Orizaba saddle. Never mind the road, this is a beautiful

area. Hiking up Sierra Negra’s east ridge we found North America’s highest

tree. My altimeter read 14,660 feet. Coastal moisture rolls up this slope,

and the rich volcanic soil nurtures many astonishing trees well over 14,000

feet. We descended into a thick fog and returned to Tlachichuca for Christmas

Eve fireworks. It was quite a celebration. |

|

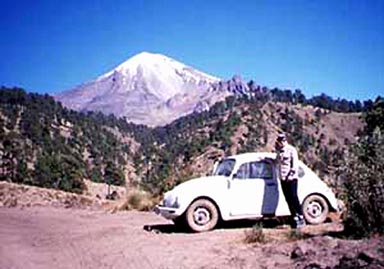

Sierra Negra from the southwest |

|

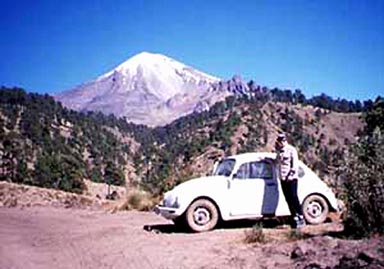

Our rent-a-bug at 12,600 feet on Sierra Negra with Orizaba’s southern slopes beyond |

|

Jennifer by North America’s highest tree at 14,660 feet on Sierra Negra

Orizaba behind |

| Toluca on the day after Christmas. We did a day climb from the Hotel Paseo

in the city of Toluca. The Paseo is right on the main highway on the east

side of town. The gourmet road up Toluca took us easily to a gate at 13,800

feet. For a small fee you can drive past the gate into Toluca’s crater, but

there is a good trail starting from the gate and there is little need for

the final drive. Our first goal was 14,600-foot Campanario, a significant

sub summit northeast of Toluca’s main peaks. This perch gives an astonishing

view of Toluca’s crater. There were many Mexican runners training here. Look

for them in the next Olympics. They didn’t break stride for Campanario. |

|

Jennifer on Campanario with Toluca’s Pico de Aguila behind |

|

Approaching Pico de Aguila’s east ridge |

| We then ascended the east ridge of

Pico de Aguila. 15,269-foot Aguila is Toluca’s north peak, and its east ridge

is a Mexican classic. The minimal Class 3 scrambling reminded us of Torrey’s

Kelso Ridge Route in Colorado. Aguila was bone dry for us, but several memorial

plaques spoke about climbers who must have found it icy. We met a solo Japanese

climber on Aguila’s summit and traded the obligatory photos. He was dismayed

when we confirmed his suspicion that Toluca’s highest point, Pico de Fraile,

was a mile south of Aguila. We invited him to join us for the traverse, but

he did not have the time. |

|

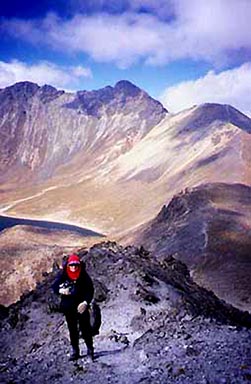

Aguila as seen from Fraile, showing the traverse |

| The traverse between Aguila and Fraile

is another Mexican classic. The ridge does not dip below 15,000 feet for a

mile, and this traverse reminded us of Evans’ West Ridge Route in Colorado,

only Toluca’s traverse is a thousand feet higher. With careful route finding,

the difficulty does not exceed Class 2+, but it is easy to find Class 3 scrambling

here. We skirted one gendarme that requires Class 3 scrambling to cross. Our

final climb to 15,433-foot Pico de Fraile took us to our expedition’s high-point.

Toluca is Mexico’s fourth highest peak, and it was our highest peak of 1998.

It was late in the day, and we had the summit to ourselves. We descended the

standard route into the old crater. |

|

Nevado de Toluca’s Pico de Fraile as seen from Campanario |

| The crater holds two large lakes, Laguna

del Sol and Laguna de la Luna. The half-mile long Laguna del Sol is at 13,780

feet, and must be the largest significant lake in North America. We did not

want to let go of our vacation so we made one more laconic ascent. We hiked

around the lake and climbed the attractive resurgent dome in the middle of

the crater, 14,206-foot Cerro Ombligo. From the summit, our 16th, we surveyed

our day’s work, let out a big yodel, then headed for Colorado. Viva Mexico!

Ajuua! |